I finally got around to reading Fareed Zakaria’s 1997 article in Foreign Affairs: “The Rise of Illiberal Democracies.” I really enjoyed his book, The Post-American World and know that he’s a big shot on CNN now. Still, this article far surpasses anything he’s done on TV or books as of late, and it opened my eyes to a very interesting concept, something I hope to expand upon in an academic article in the future.

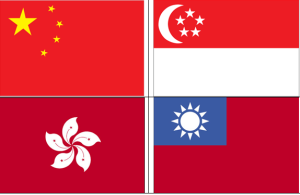

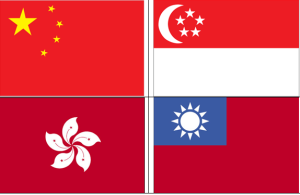

Zakaria notes somewhat indirectly how Hong Kong and Singapore, both majority Chinese and former British colonies, took very different paths in political development. Immediately I got to thinking about the other two “Chinas,” Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China. They too took very divergent paths in political development. Combined, we have the four majority-Chinese states in the world, each taking a markedly different path. How did this happen? Is Chinese culture really that universal? Or is “Chineseness” simply a farce, at least in political relations? Using some of Zakaria’s terms, I want to look closer into this question.

Zakaria uses the term “illiberal democracy” to define a country that has elections, but they mean close to nothing. “Illiberal” in this sense does not mean conservative, but rather refers to the opposite of classical liberalism. Way before we had the left versus the right, we had royalists versus classical liberals. Liberals like the Founding Fathers believed in freedom of speech, religion, press, and most importantly, rule of law (generally in a constitution). An “illiberal” state, therefore, would have laws made up by the leaders on a whim, limited freedom of the press, and other restrictions on personal expression.

The other half of the phrase, “democracy,” simply refers to popular choice of one’s leaders. After World War II, most countries decided elections were a good thing, even if they were rigged. This would be an illiberal democracy. An autocracy, on the other hand, has no meaningful elections to speak of. Very little is done to imply that the people have any choice, or the elections are for trivial offices. Most authoritarian nations today have rigged elections, or find some way to otherwise suggest they are democratic. The “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” tries for a double whammy, implying both “the people” and “democracy” are involved. In this case, they appear to be overcompensating for their exceptionally oppressive form of government.

This is hardly an exhaustive report, but rather a brief summary. First, Singapore:

Read the rest of this entry »